Why Black Holes?

I was chatting with a friend over some kind of caffeinated beverage when he asked me, “Why Black Holes?” Here is my response–after I said, “Seriously. You haven’t read my books?”

In this opening dispatch on black holes, ironically, there wasn’t enough spacetime for a deep exploration into every theme, many of which you can find in the wee-little Black Hole Survival Guide by yours truly. This brief missive casts a sky-wide view but glances past a multitude of conceptual goldmines, every one abundant with implications for the universe, many of which could be entire dispatches on their own–and will be. Over the coming weeks, I’ll single out ideas that were grazed tangentially here, diving deeper into each. So if you feel your grasp on the meaning of an event horizon isn’t what it could be to survive an encounter, then stay tuned. Event horizons deserve their own article. If you are not familiar with Stephen Hawking or his endlessly prodigious ideas, fear not. Help is coming. Or, if instead, you are tremendously confident in your grasp of the crisis facing quantum gravity, there will be provocations for you, too. I have spent a lifetime in conversation with physicists, astronomers, and mathematicians on the big bang, black holes, spacetime, and quantum mechanics. We all tell the story differently and there are unanticipated insights in every exchange. Join the conversation and the community and please endorse science everywhere–but especially right here! Consider becoming a paid subscriber to support my underlying scientific research which ultimately fuels these dispatches.

Welcome to Dispatches from the Universe — Janna

In the movie adaptation, I want a black hole to creep ominously across the screen, a soulless villain, Vantablack consuming my field of view, a sub-woofer rumbling so powerfully my whole torso resonates. I want to experience a modicum of the terror of falling into that obliterating darkness. I want to dabble in the existential dread, if only for the rebound elation when the house lights go on.

I suppose black holes deserve a bit of that bad rap. They are brutally unforgiving. There is no negotiating. But the type casting as the ultimate malefactor is not entirely fair. I often go to some trouble to shuck away the misapprehensions about black holes, secure them a more prideful place in the astronomical story. More a flawed hero than an irredeemable nemesis.

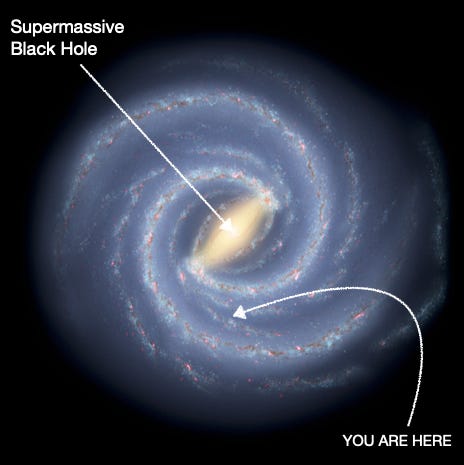

Our entire solar system orbits a supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy roughly once every 250 million years. The last time we were at this location relative to that black hole, dinosaurs had not yet roamed the Earth. Sag A* — pronounced “SADGE-ay-STAR”, so-named for its location beyond the constellation Sagittarius —at nearly 4.5 million times the mass of our sun still has not destroyed the galaxy, nor has Sag A* vacuumed us up into oblivion. Our orbit, way out here in a sparse region between spiral arms of the Milky Way, is perfectly stable. Perfectly safe. I would go so far as to say we owe a debt of gratitude to Sag A* for sculpting the galaxy billions of years ago in such a manner that there are habitable outskirts like the one we find ourselves in.

Generally, I advise letting black holes just be. You leave them alone, they’ll leave you alone. They are in fact utterly impassive. Left to their own devices, they do not rumble, inflame, churn, destroy. In a profound sense, isolated black holes do not change at all. They are entirely quiescent. Every instant indistinguishable from the last.

This should give you pause.

You and every material thing around you endures continual change. Breathing, metabolizing, growing, eroding, photosynthesizing, shifting in winds. The changing seasons. The tides. Solar storms. The Sun roiling through magnetic cycles, spots swimming and merging in the solar atmosphere. On astronomical timescales and glacial timescales, geological timescales and nanosecond timescales, things change. We navigate a world of composite stuff, built out of smaller elements down to microscopic particles and those elements permute and interact, fluctuate and realign so that all composites are forever restless and transforming.

Not black holes. In principle, a pure, isolated black hole is formally, mathematically timeless.

Not just timeless. Also featureless. A black hole of a certain charge, mass, and spin is indistinguishable from any other black hole with exactly that charge, mass, and spin. Suppose you discover a black hole and you want to plant a flag, literally. So you jab a flag into the event horizon, then somehow make your escape. Not only will the signage fall into the black hole, all the markings and information—the nation you hail from, the year of your expedition, the colors and symbols of your culture—fall in as well. No blemish, no detail, from that flag can possibly remain to be gleaned from the outside. The event horizon refuses to reveal any evidence of the signpost you tried to plant for other travelers. You cannot lay claim to that black hole, which hides all except its charge, mass, and spin. The history of its formation, the details of all that fell in, forever sealed behind the black hole’s shadow.

In this regard, black holes are reminiscent of the fundamental quantum particles encountered as we magnify the world and zoom down to microscopic scales, down to the elementary constituents of all things. A profound principle of quantum mechanics asserts that fundamental particles are utterly indistinguishable. Consider the electron. Every electron is indistinguishable from every other. All of the electron’s defining characteristics–such as its mass, charge, and spin–are precisely identical to every other electron’s. You cannot tag them with any identifying markers. An electron in your body is interchangeable with an electron from an asteroid. These fundamental, quantum elements are featureless. They are also timeless. They do not degrade over the lifetime of the universe. You cannot tell how old an electron is.

Remarkably, black holes share that timeless, featureless aura. Unlike the electron, black holes come in a spectrum of masses, charges, and spins. But those three numbers are all you need to know in order to know everything you can possibly know about that black hole.

Black holes and only black holes, maintain this austerity on colossal, macroscopic scales. Perhaps black holes aren’t similar to fundamental particles, rather they are fundamental particles—elementary particles of Quantum Gravity. So, why are black holes the most compelling, fascinating, alluring phenomena in the universe? Behind those frustrating, impenetrable event horizons might be the promise of the holy grail of theoretical physics since Max Planck presented his quantum hypothesis in 1900, Neils Bohr mused about the atom, Werner Heisenberg asserted a foundational uncertainty principle, and Einstein considered the particulate nature of light. Black Holes harbor the cipher to a Law of Quantum Gravity.

Now, if you are aware of the famed Stephen Hawking and his comparably famous discovery of black hole radiation, you may call foul. Black holes ultimately evaporate and therefore are not strictly timeless and if the radiation encodes information otherwise sealed behind the event horizon, black holes are not strictly featureless either, which would seem to contradict all of our previous assertions. However, the manner in which black holes radiate and reveal information—or not—must be quantum gravitational. There black holes are again, providing the terrain for quantum gravity. And that’s the significant takeaway: black holes and quantum gravity are inextricably intertwined.

If black holes are indeed fundamental particles, then they must exist as part of nature’s essential inventory. We expect tiny, microscopic black holes to be created in the early universe along with the rest of the quantum ingredients in the primordial soup. They could be a byproduct of powerful enough supercolliders both human-made and naturally occurring or of high-energy collisions of cosmic rays in the Earth’s atmosphere. The stunning turn of events in the history of the cosmos is not the existence of black holes but rather that nature imagined a way to make them so big – astrophysical black holes on macroscopic scales as the death states of stars, fundamental quanta of gravity as heavy as suns.

As protagonists, black holes are fraught with contradictions. An unholy abyss and a fount of revelations. By the vast numbers—by the billions of billions—hauntingly inconspicuous and benign, yet violent and lethal when provoked. Flawless as quantum particles yet big as cities, planets, or even solar systems. Alluring yet terrifying, endlessly fascinating and mesmerizing in every scene.

Substack posts (like this one) are similar to black holes: Readers fall into them and don't come out. Only this could explain why readers haven't commented (can't comment!) on this beautiful and bewildering post. (How am I commenting, you ask? I sent a probe to read the post for me and report back just before it passed the event horizon. It said the article was applauditory and I take the probe at its word.)